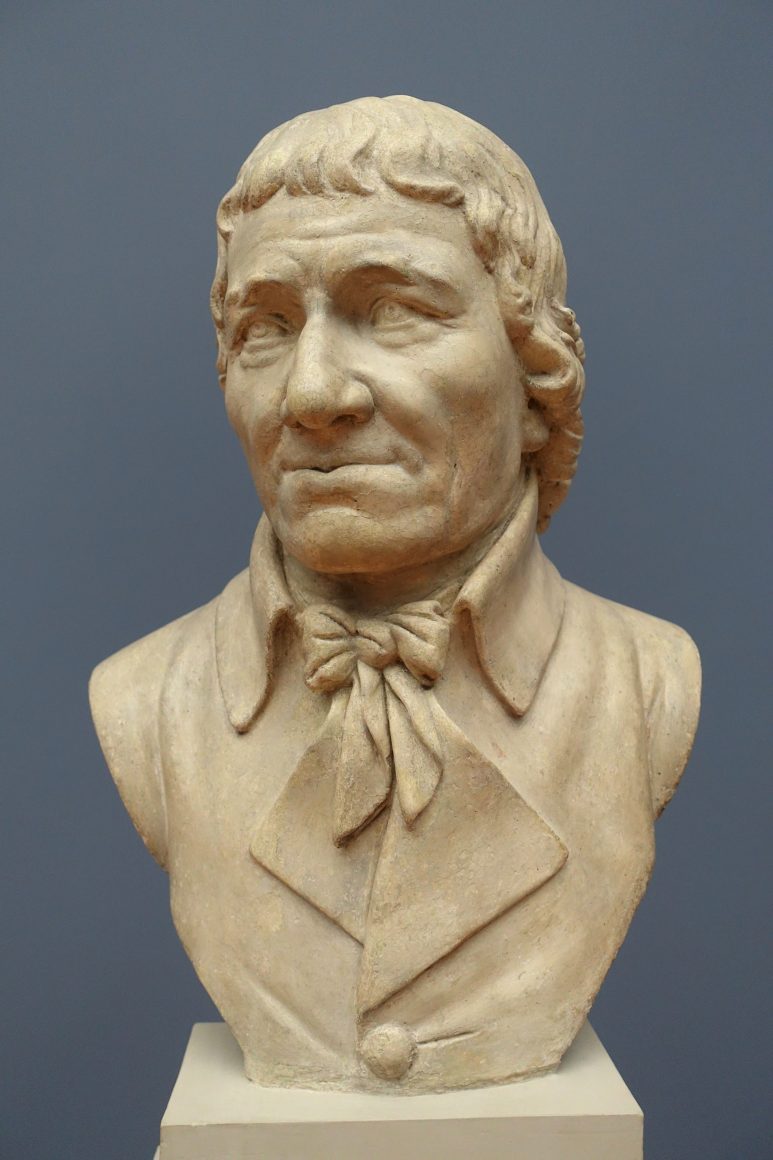

A PORTRAIT

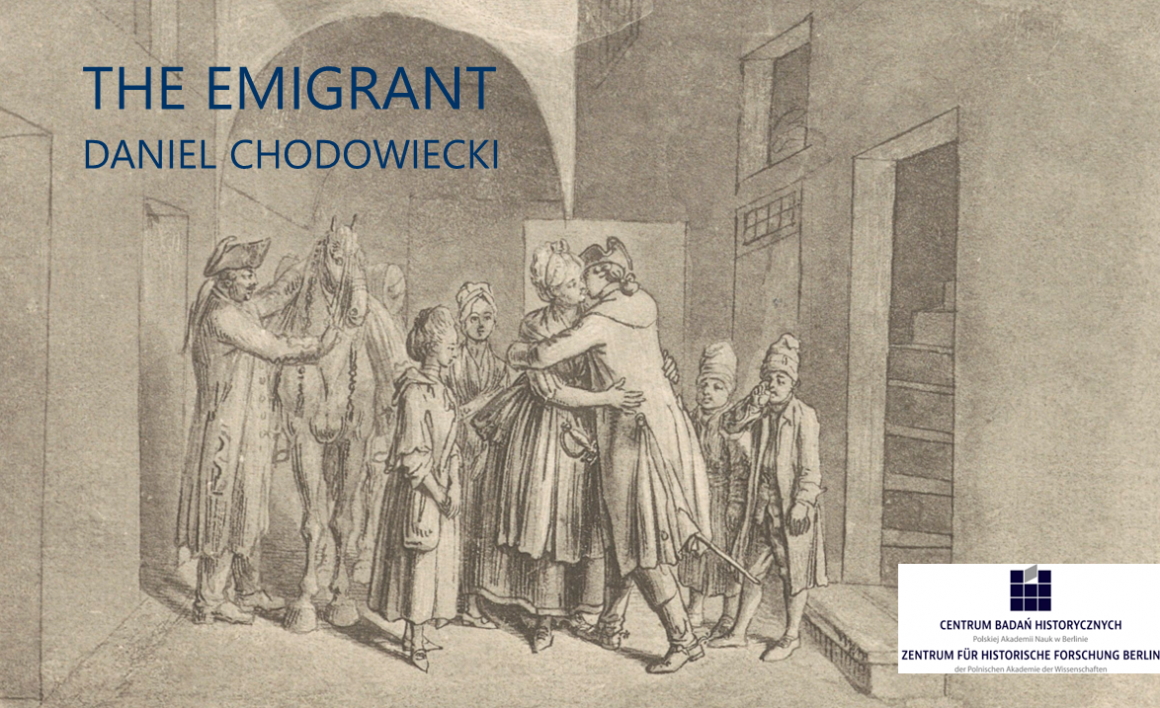

In one of the rooms of the Bode Museum in Berlin, visitors may come across a sculptural portrait of Daniel Chodowiecki. However, the inscription beneath the bust does not specify who this man with a Polish-sounding name actually was. In fact, Daniel Chodowiecki (1726–1801) was one of the most renowned artists of the 18th century. As a teenager, he left his hometown Gdańsk in Poland and moved to Berlin in Prussia, where he achieved a great artistic success. The experience of migration influenced his entire life and left traces in his art. This online exhibition is devoted to that experience.

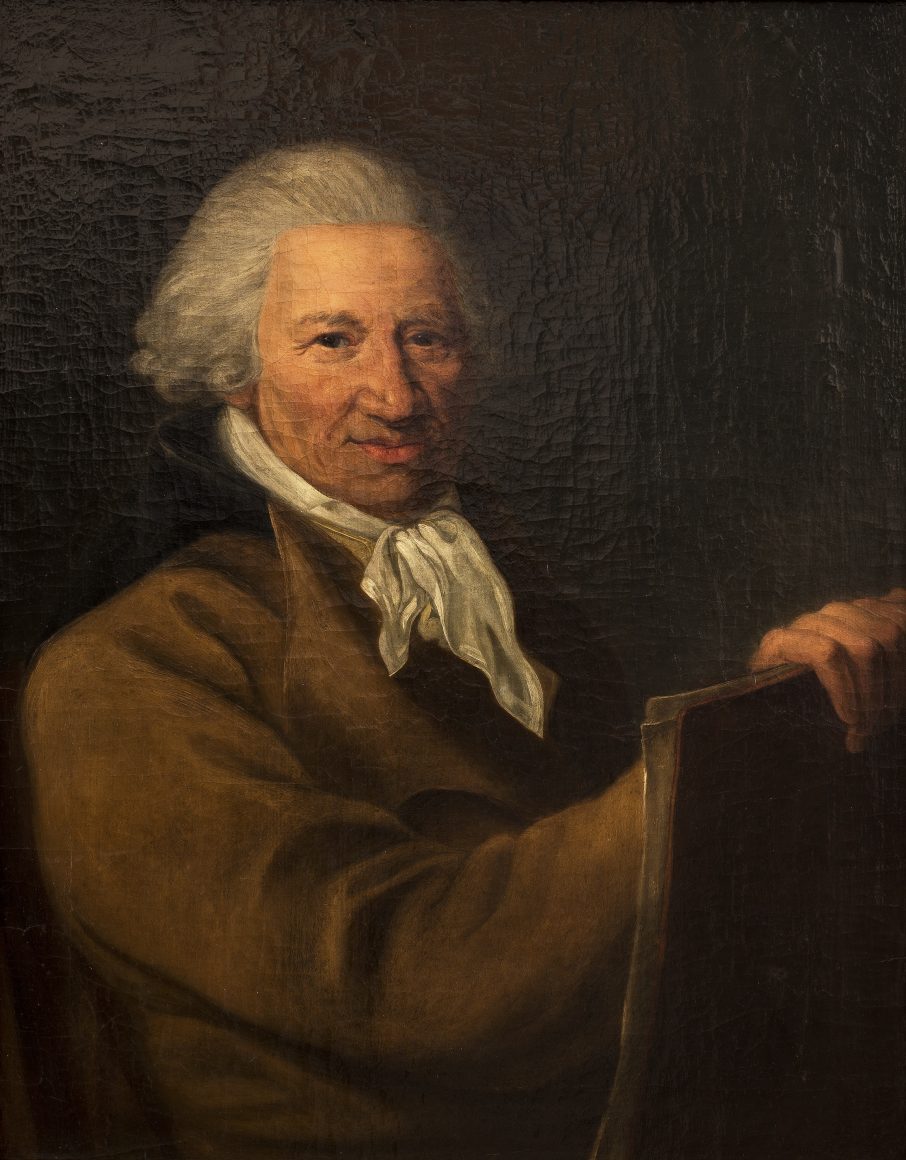

The plaster bust depicting Daniel Chodowiecki is evidence of his high social status. This type of portrayal was reserved for outstanding, accomplished, or very wealthy citizens. Many portraits of Chodowiecki have survived, especially engraved and painted – created by him as well as by other artists. You will see some of them in this exhibition.

Emanuel Bardou, Portrait of Daniel Chodowiecki, 1801, plaster, Bode Museum, Berlin

Back

Back