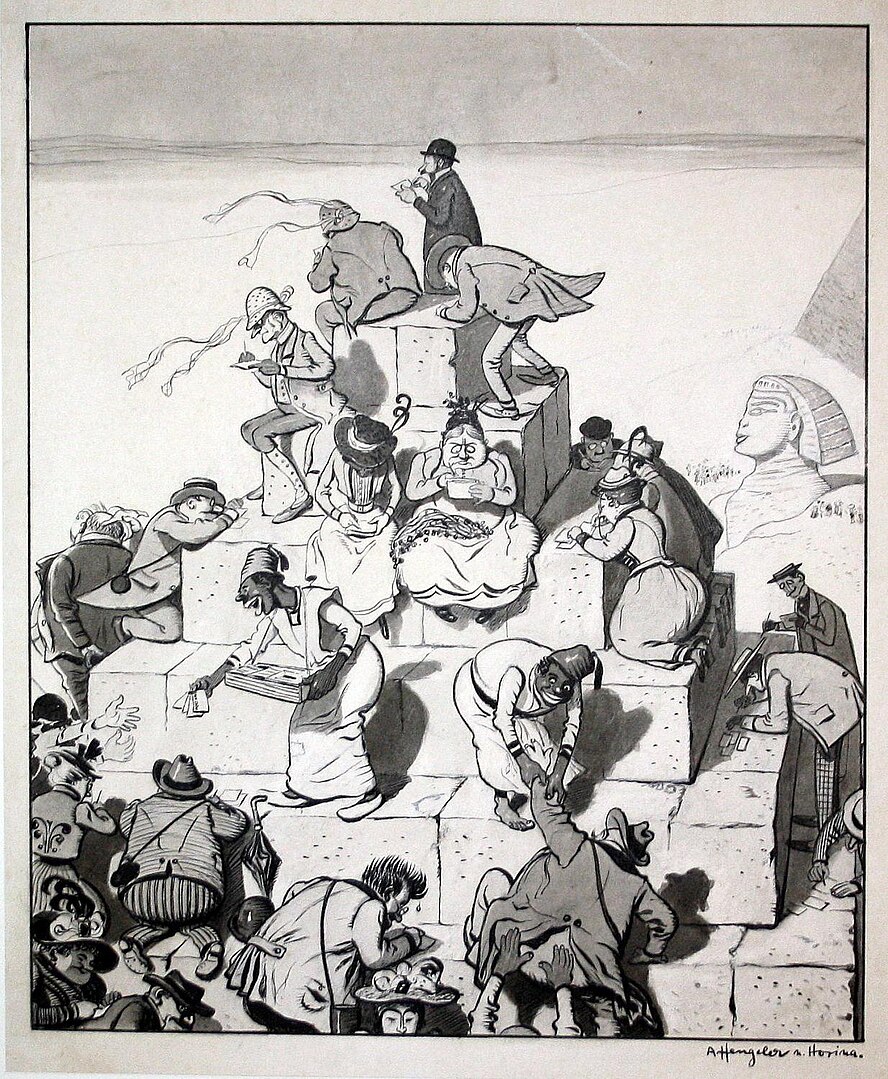

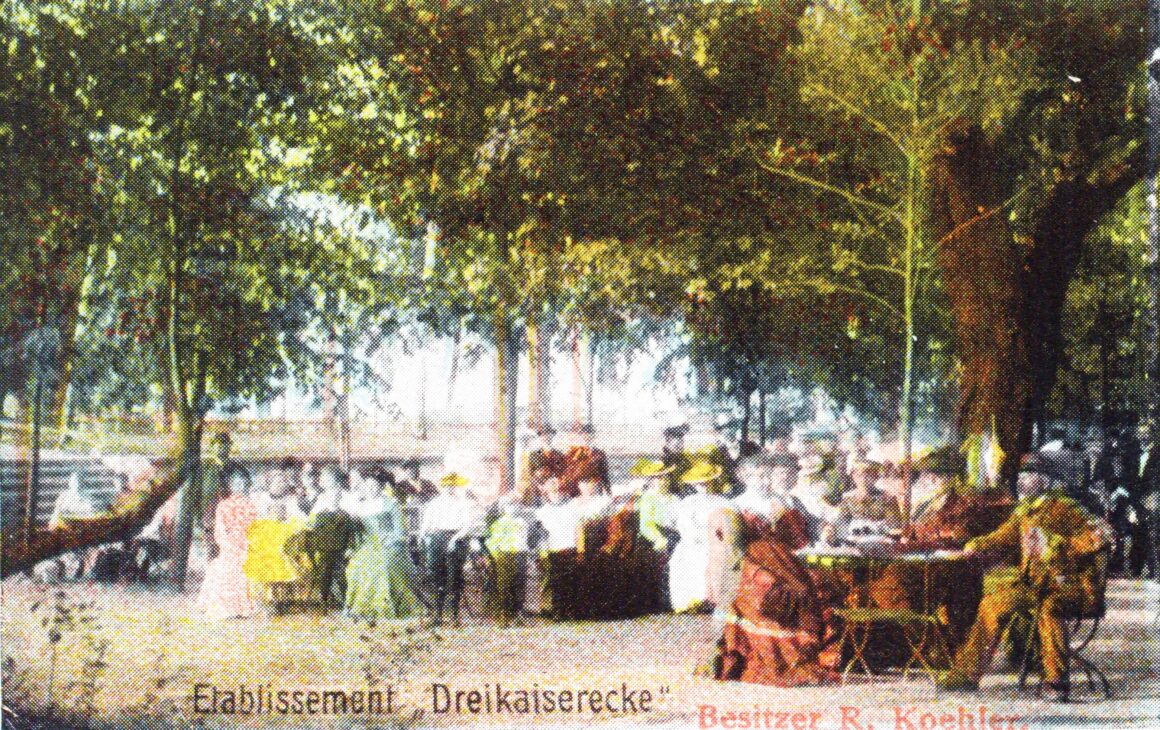

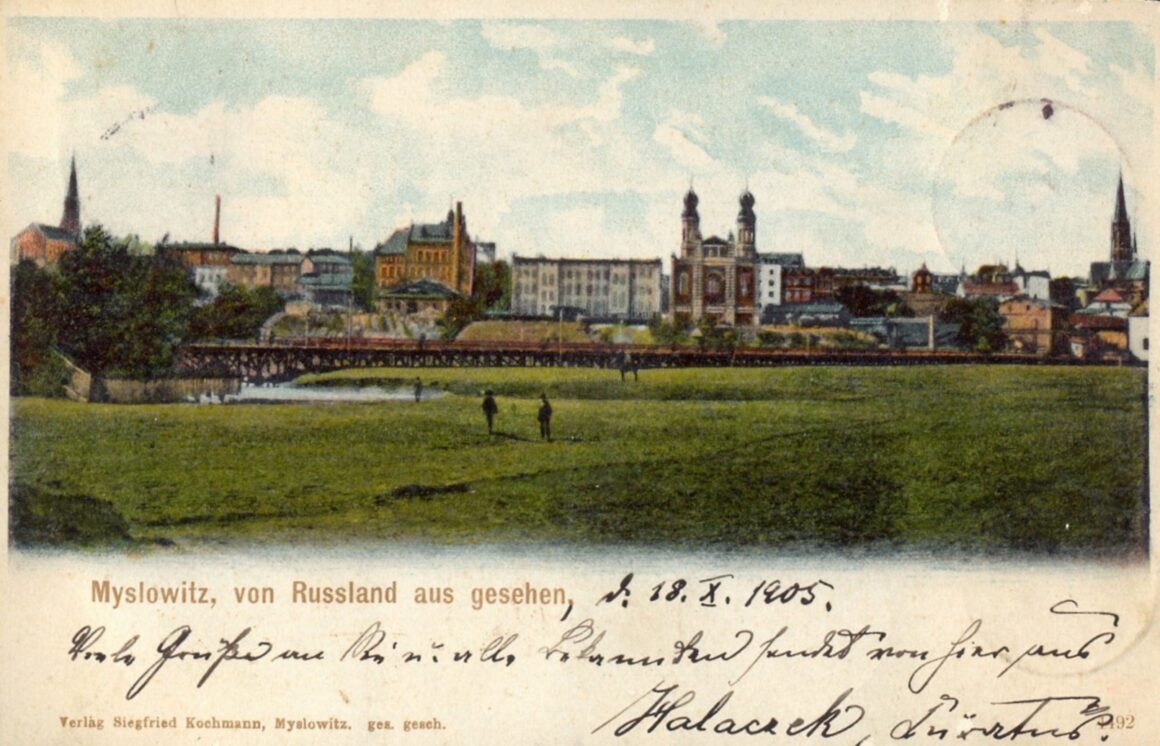

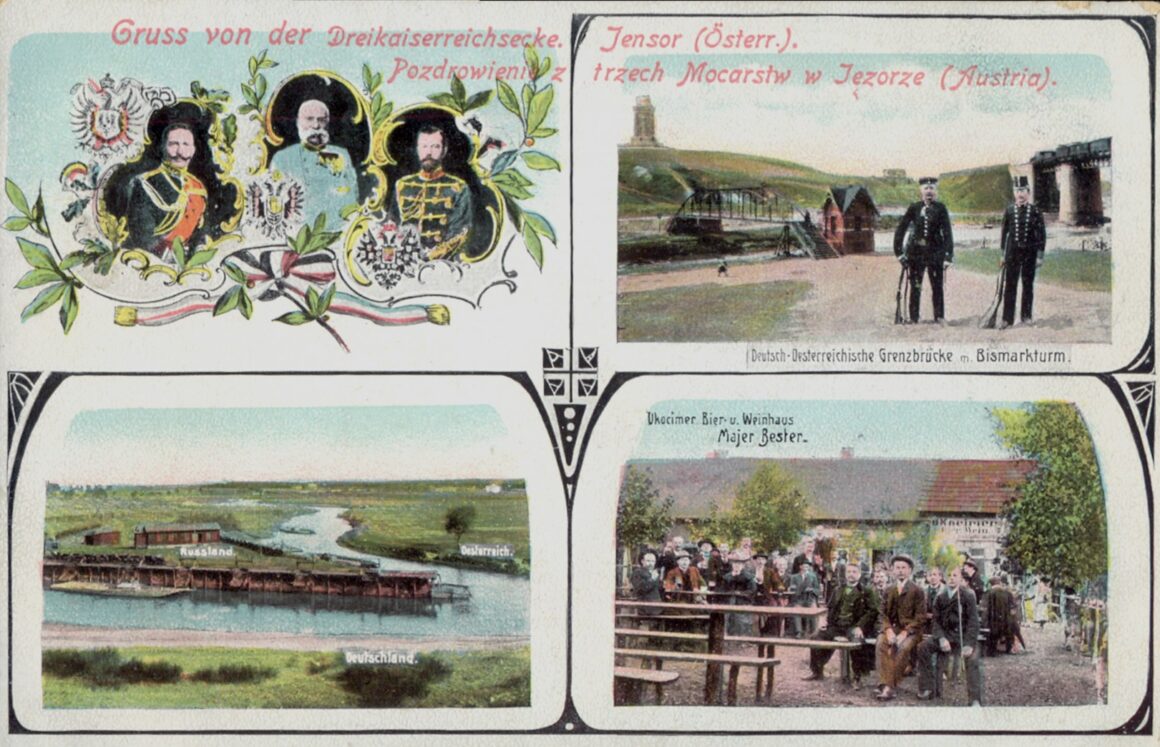

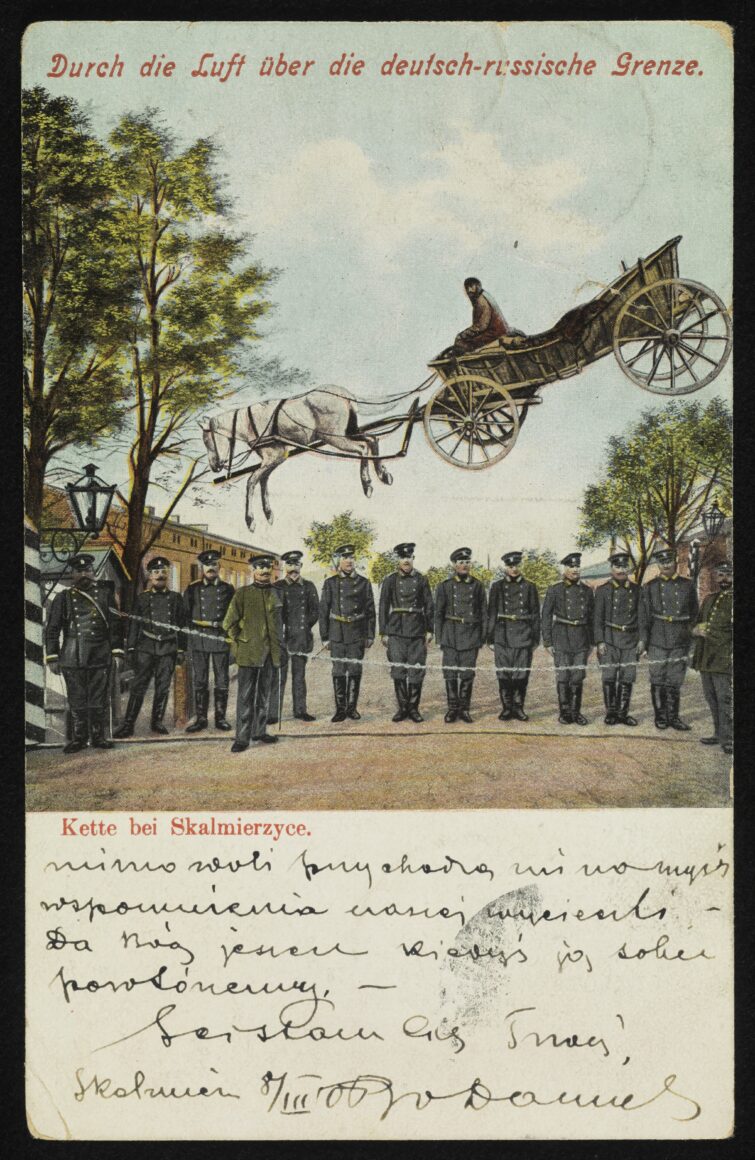

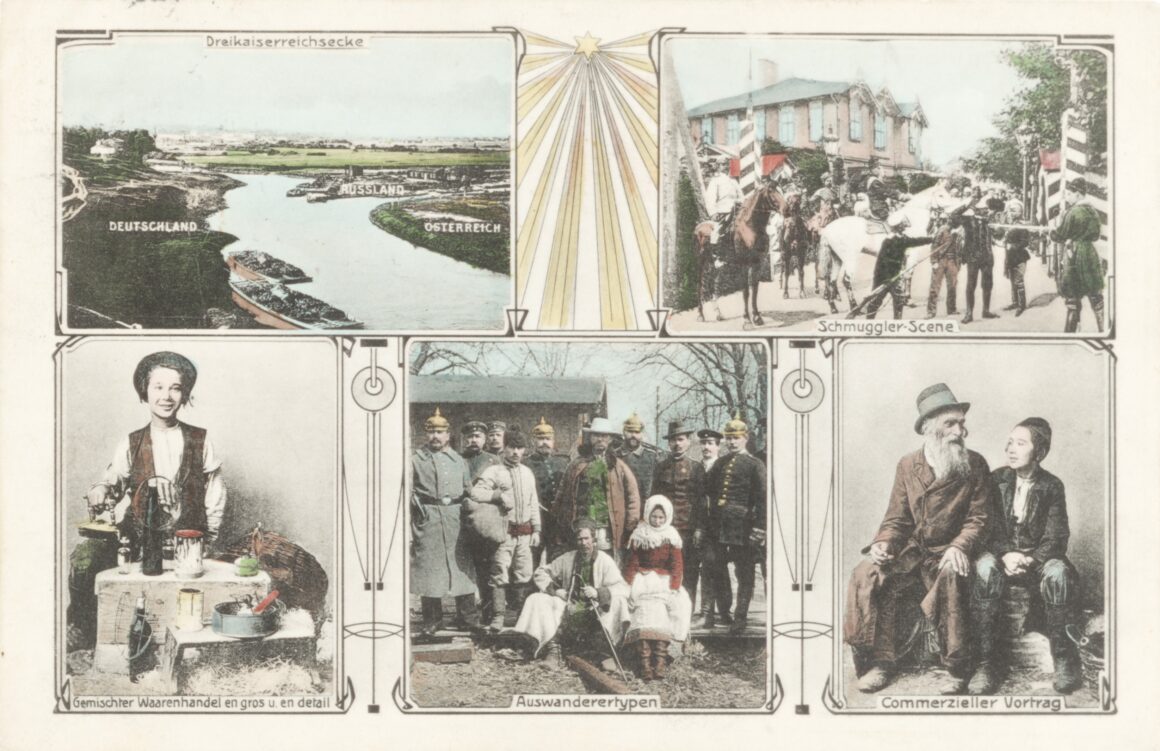

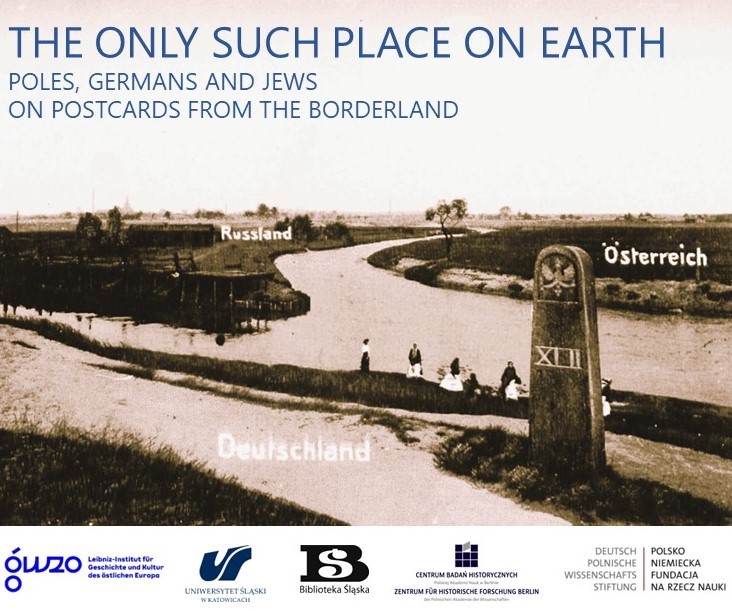

“The only place on earth…” – with these words on the above postcard the description of a unique place on the map of Europe begins: the Corner of the Three Emperors. It was the meeting point of the borders of Prussia, Austria and Russia in Upper Silesia near the town of Myslowitz where these countries were neighbours from 1846 to 1915. Today, Myslowitz is known as Mysłowice and is located in southern Poland, but in those days, it lay at the eastern end of the German Empire on the route of legal and illegal migration of thousands of people from Eastern Europe to the West. However, the Corner of the Three Emperors was much more than a transport route: it was a tourist destination, a centre for the transfer of goods and an object of propaganda. Hundreds of postcards from the late 19th and early 20th century, which were used for more than just private messages, attest to the uniqueness of the place.

Corner of the Three Emperors, published by H. Lukowski, Wrocław, 1913 (?)

Silesian Digital Library, private collection

Back

Back