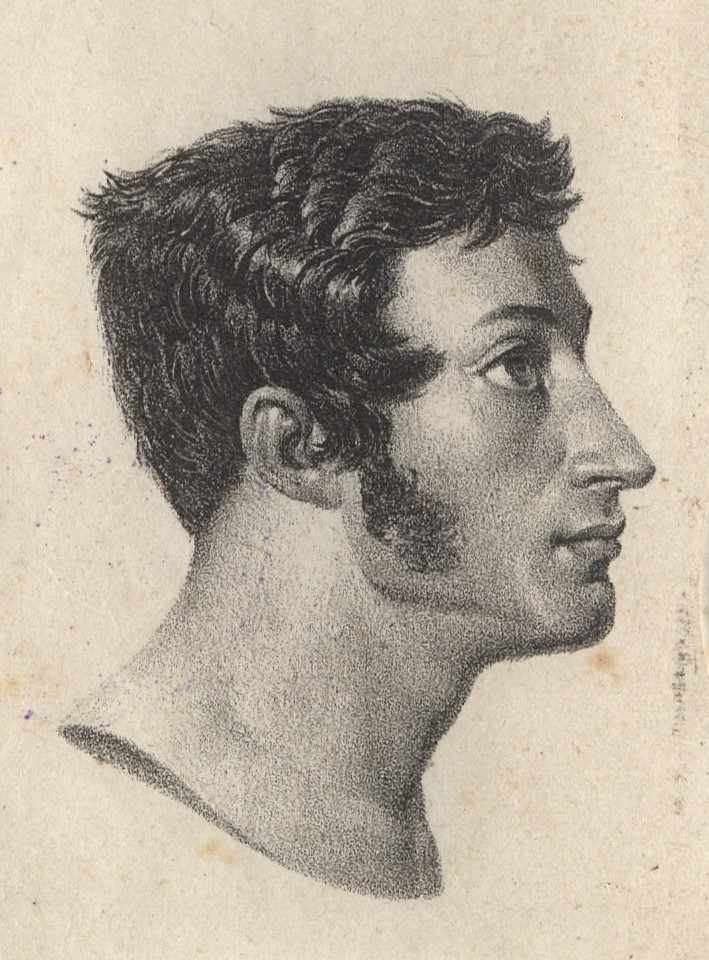

A national epic. A great work of Romanticism. An obligatory school reading. Almost 200 years after the premiere of Pan Tadeusz (meaning Sir or Master Thaddeus), the epic poem by Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855), is known to almost everyone in Poland, although everyone associates it a little differently. Nonetheless, most Poles would probably confirm that Pan Tadeusz holds a supreme position in Polish literature. It is not without reason that Mickiewicz was honoured at an early age with portraits like the one above, and also with monuments after his death. And an entire museum in Wrocław was even dedicated to Pan Tadeusz. But does the work evoke any associations in Germany, for example? Did it have or has it any chance of breaking through into the German consciousness? In this online exhibition we will look for answers to these questions.

Pictured: An anonymous portrait of Adam Mickiewicz included in his collection of Poezye, or Poems, published in Vilnius in 1822. The poet was 24 years old at the time.

National Library in Warsaw

-

-

But first, a brief summary of the plot of Pan Tadeusz. The story is set in 1812 in the small village of Soplicowo in Lithuania. The area previously belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but at the end of the 18th century, as a result of the partitions, it came under Russian rule. There is a conflict between Polish noblemen from Soplicowo over the local castle – you can see the scene of a brawl between them in the illustration above. Parallel to this dispute plays out the love story of young members of the feuding families: the titular Tadeusz and Zosia, who falls in love with him.

Pictured: A fight between noblemen in Soplicowo in an 1882 engraving by Michał Elwiro Andriolli. This sought-after book illustrator was friends with Adam Mickiewicz’s son, Władysław.

National Library in Warsaw -

As the dispute between the noble families gains momentum, they suddenly come to their senses: they realize that instead of fighting each other, they should turn against a common and real enemy — the Russians. United, they drive the Russian soldiers out of Soplicowo, or symbolically – out of Poland. In turn, the two families will henceforth live in harmony, and their bond will be strengthened by the marriage of Tadeusz and Zosia.

Pictured: The residents of Soplicowo moving against the Russians on Michał Elwiro Andriolli’s 1882 engraving. A progressive count rides alongside a traditionalist nobleman, symbolizing the unification of Poles across differences.

National Library in Warsaw -

When Adam Mickiewicz published Pan Tadeusz in 1834 while in exile in Paris, the epic’s message was clear. On the one hand, it contained a patriotic call to unite Poles and regain independence. On the other hand, the text showed the range of attitudes of Polish society, especially the nobility, during the partition. It clashed conservatism and progressivism, parochialism and cosmopolitanism, quarrelsomeness and readiness to compromise, loyalism and rebelliousness.

Pictured: A Polish nobleman depicted by Jean-Pierre Norblin de la Gourdaine in an 1818 engraving. A French artist who settled in Poland, Norblin illustrated the lives of Poles with fascination, but also with a touch of wit.

National Museum in Warsaw -

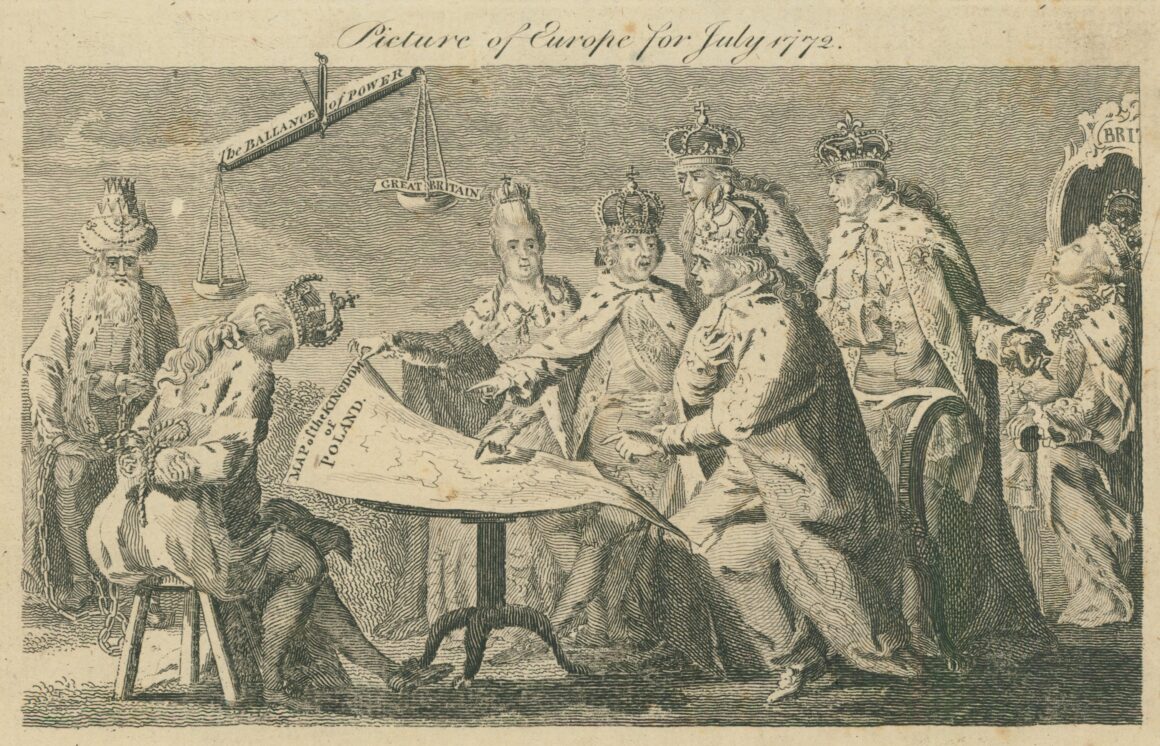

The qualities of the Poles had a better or worse impact depending on the circumstances. However, they receded into the background when the need to unite in difficult times took precedence. Unfortunately, the unification of Poles was often overdue. Such was the case at the end of the 18th century, when the Poles, wanting to prevent Prussia, Austria and Russia from imminent partition, passed a constitution to reform the weak state. Too late. The saying “A wise Pole after the event,” coined back in the Renaissance by poet Jan Kochanowski, was still relevant.

Pictured: Anonymous English engraving with allegorical scene of the first partition of Poland in 1772. The rulers of Russia, Prussia and Austria divide the country between them, while the Polish king like a hostage sits with his hands tied.

National Library in Warsaw -

To this day, the contradictory qualities of the noblemen of Soplicowo define the thinking of many Poles about themselves. Mickiewicz, a representative of the generation “born in captivity” and rebelling against oppression, became an exponent of Polish nature, memory and fate. Pan Tadeusz sank into the collective consciousness of Poles. This was influenced not only by the eloquence of the work, but also by its admired poetic form, reflecting the author’s literary artistry and lyrical longing for the lost homeland.

Pictured: Ruins of the castle in the Lithuanian town of Trakai in a painting by Wojciech Gerson from 1855. The native Lithuania in Mickiewicz’s memories and works is mainly idyllic landscapes, traces of former splendour and local beliefs.

National Museum in Warsaw -

Many other work by Mickiewicz focused on the question of regaining independence. The poetic drama Dziady, or Forefathers’ Eve, revealed Mickiewicz’s philosophical and political concept of the Polish nation. According to it, the Poles, after years of persecution, were to play a major role in the restoration of freedom and justice on earth.

Pictured: Gustaw, one of the protagonists of Dziady, in an 1896 illustration by Czesław Borys Jankowski. Struggling with himself on the edge between the world of humans and spirits, Gustaw undergoes a transformation from an unhappy lover into a character named Konrad, a fighter for the nation’s freedom.

National Library in Warsaw -

Mickiewicz and other writers of his time developed a specifically Polish variant of Romanticism. Its main components were the desire for freedom, national solidarity, sacrifice, and moral superiority over imposed authorities. According to Maria Janion, a prominent researcher of Romanticism, the pursuit of freedom and independence became the source of the value system of Poles until the end of the 20th c.

You can learn more about Maria Janion and her interpretation of Romanticism from the above recording of the debate (in German), which we organized in 2020. -

Romantic values mobilized Poles to resist the partitioners in the 19th century, regain independence in 1918, fight the Germans during World War II and resent the communist rule imposed after the war. One example of the mass unification of Poles was the Solidarity social movement, whose manifestation you can see in the 1980 photo. Only the fall of communism and the regaining of sovereignty in the late 1980s and early 1990s weakened the romantic set of values. According to many, it simply ceased to be necessary.

Pictured: A demonstration in support of Solidarity during the 1980 strike at the Gdańsk Shipyard, photographed by Zenon Mirota. Some interpreted Solidarity as a legacy of Romanticism. Learn more about this social movement from the materials on our website.

European Solidarity Centre in Gdańsk -

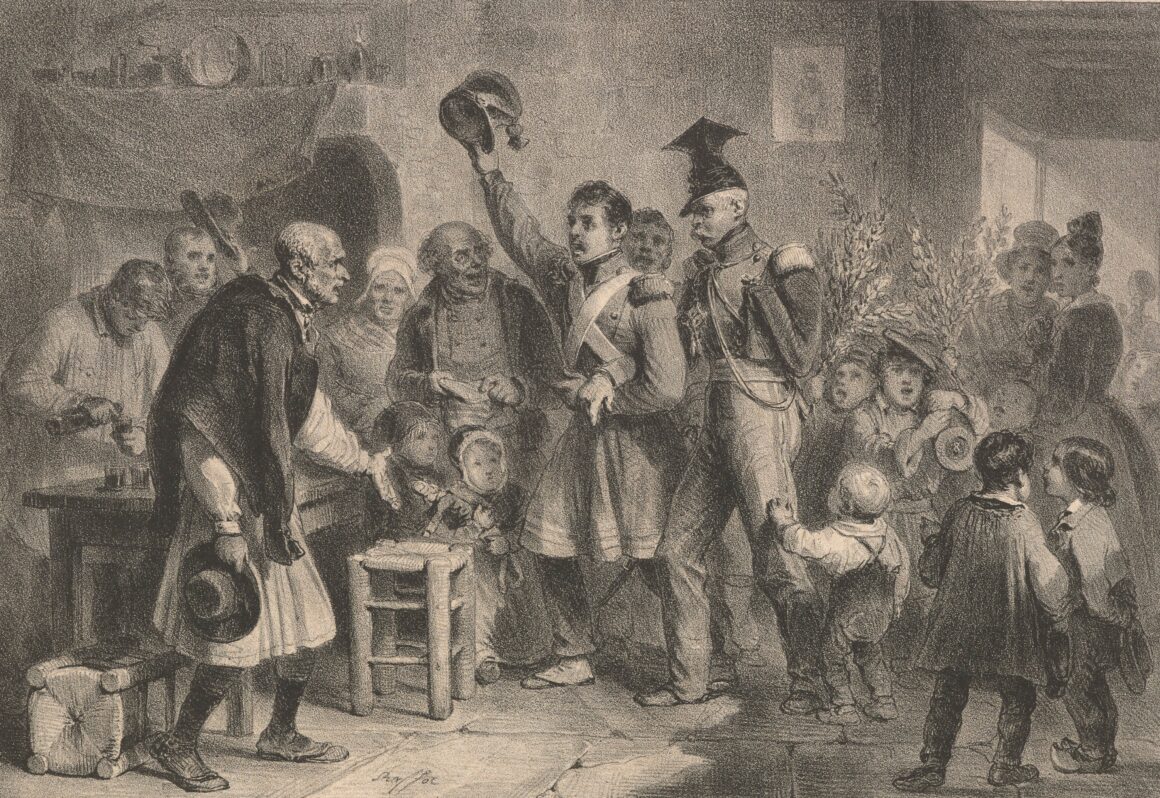

Romantic values, however, were sometimes criticized. Already in the 19th century, part of the Polish elite relied on “grassroots work”: building the position of Poles under the partitions by small steps, rather than revolts and battles. Critics saw in romantic ideas the source not of heroism, but of inadequate emotions and miscalculations that stood behind failed Polish uprisings against the partitioners, especially the Russians. These revolts ended in repression of Poles and their mass emigration to the West. At the same time, for part of the population the uprisings became an object of worship, and the fallen became martyrs.

Pictured: Welcoming a Polish emigrant in an inn in France on a lithograph by Denis Raffet from c. 1831. After the fall of the November Uprising against the rule of the Russians in 1831, thousands of Poles spread across Europe. Those who were already in exile, such as Adam Mickiewicz, had no way to return to their homeland.

National Library in Warsaw -

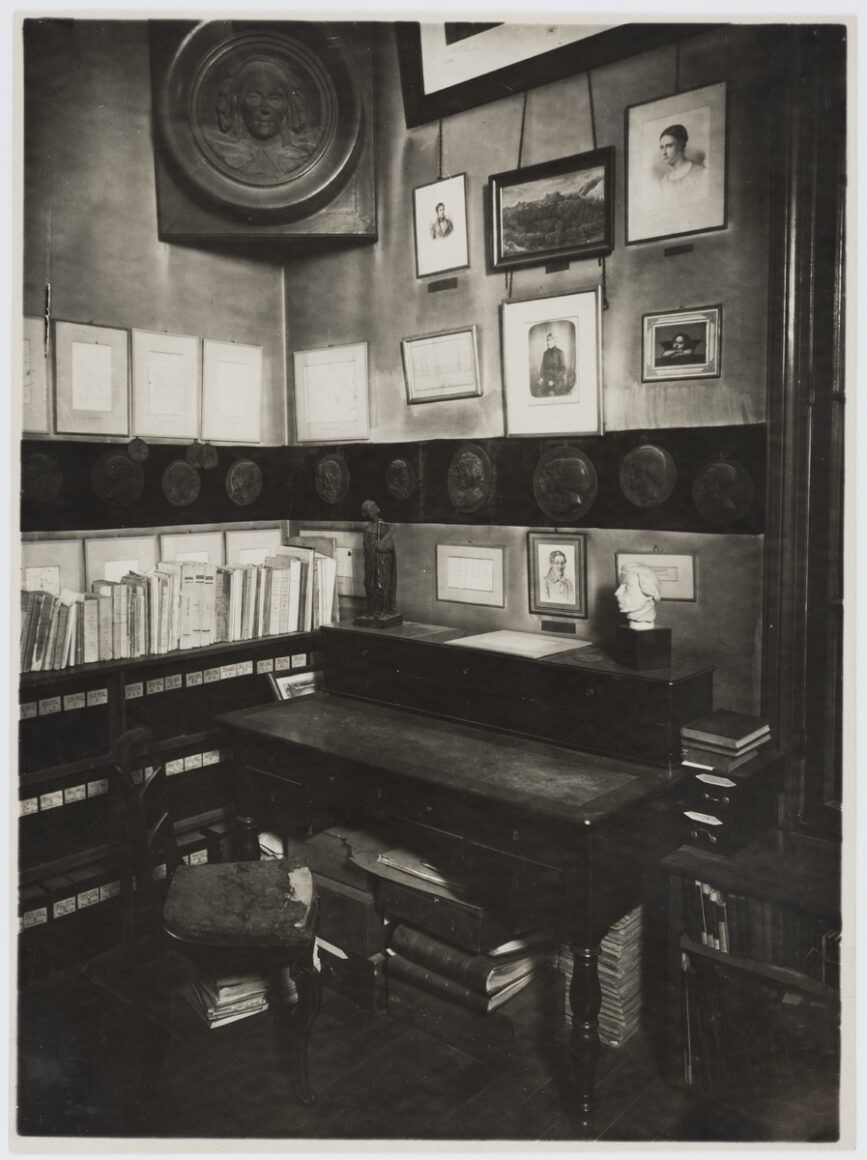

Confronting the legacy of Romanticism has become part of Polish culture. In his 1999 film adaptation of Pan Tadeusz, Andrzej Wajda encapsulated Mickiewicz’s tale in a depressing plot bracket showing the poet surrounded by Polish émigrés in Paris, for whom he reads his epic. In this version, the story of the noblemen of Soplicowo is a fable about a lost homeland that Poles were unable to save, while emigration is not an opportunity, but a brutal consequence of quarrels in the nation.

Pictured: Adam Mickiewicz’s desk, at which he wrote Pan Tadeusz in his Paris apartment. Years later, the desk went to the poet’s museum in exile in Paris. It was founded by his son Władysław in 1903 and this photo was taken there in the 1920s.

PAUart – Catalogue of Artistic and Scientific Collections of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences -

Did Pan Tadeusz, with its cultural and emotional weight, have a chance to make its mark on German readers? The first German translation of the work, titled Herr Thaddäus, appeared in 1836, just two years after the original was published. Subsequent full translations of Pan Tadeusz appeared more than a quarter of a century after Mickiewicz’s death: two versions, by Albert Weiss and Siegfried Lipiner, were published independently from each other in 1882.

Pictured: The title page of the first German translation of Pan Tadeusz, published in Leipzig in 1836. Mickiewicz was not happy with the work of translator Richard Otto Spazier, who falsely claimed to have worked on the German version together with the author.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich -

Subsequent German translations of Pan Tadeusz were published in 1921 (Robert Steingraber), 1955 (Walter Panitz), 1863 (Hermann Buddensieg) and 1977 (Walburg Friedenberg). The translation by Buddensieg, a lover and populariser of Polish literature, is considered the best today. At the same time some plans to translate the poem never materialized – such was the intention, among others, of Lina Morgenstern, 19th-century author, activist and a transplant from Wrocław (then Breslau) to Berlin, who is the protagonist of one of the episodes of our podcast.

Listen to the podcast (in the German version) by clicking on the player above. -

With so many available translations German readers have had plenty of time and opportunity to familiarize themselves with Pan Tadeusz. Yet the work did not meet with their interest. Its Polish patriotic message was too different from the perspective of the people of Prussia or Austria – countries that had jointly annexed Polish lands with Russia and had no interest in promoting Polish freedom slogans. Sporadic interest in the Poles, especially combined with sympathy on the occasion of failed uprisings, won out in German-speaking societies with distance, incomprehension or dislike.

Pictured: An engraving by Johann Carl August Richter showing Dresden in 1830. There was a Polish emigrant colony here. One of the emigrants was Mickiewicz, who stayed in Dresden from 1831 to 1832.

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden -

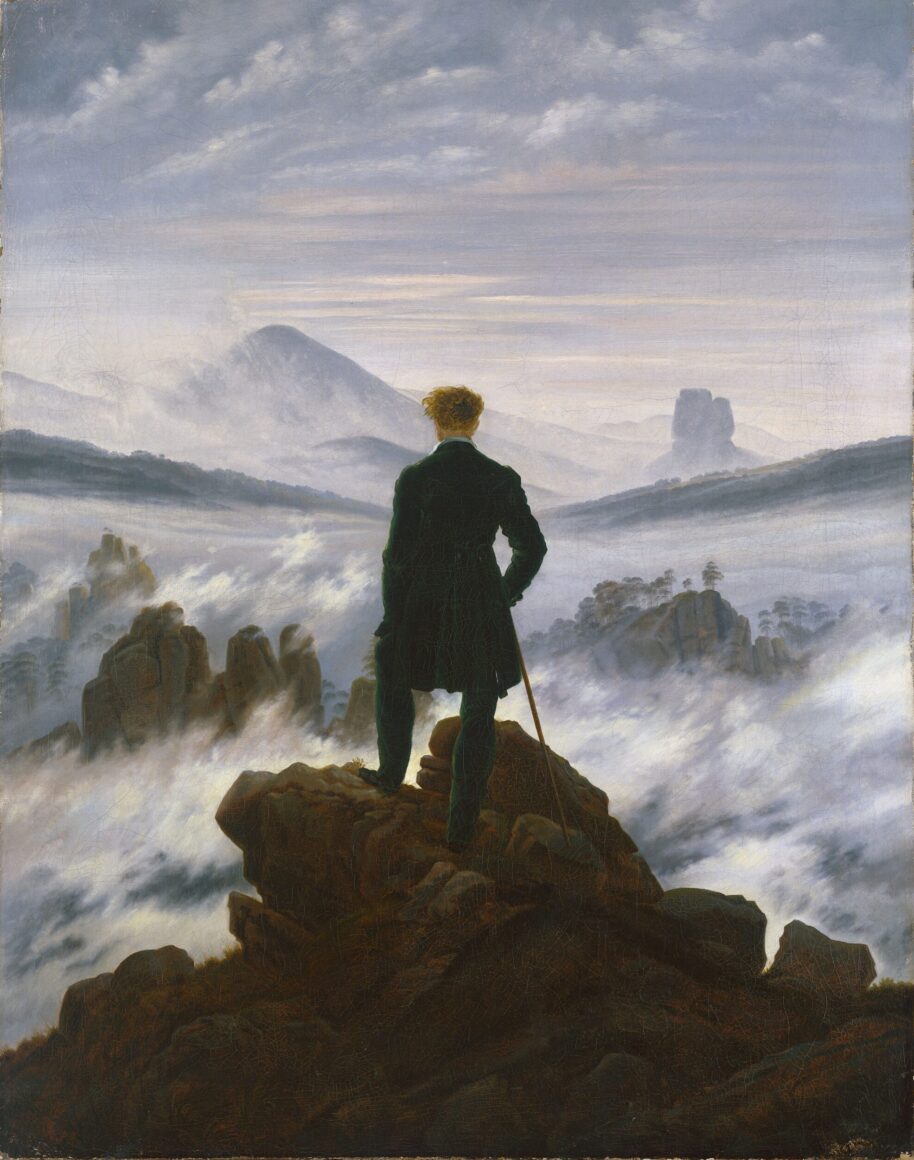

There was also another reason for the lack of interest in Pan Tadeusz and other Polish works among German readers. Polish Romanticism was different from German Romanticism, and significantly so. First, chronologically: when, around 1820, the works that bore Romantic characteristics appeared in Polish literature, painting and music, in the German sphere Romanticism – which had lasted for three decades – was actually already dying out.

Pictured: Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Wanderer at the Sea of Mists from 1818. This painting is emblematic of late German Romanticism. It focuses on a man confronted with his own feelings and the forces of nature.

Hamburger Kunsthalle -

Unlike Polish Romanticism, its German variant did not play a major role in shaping and integrating society. This function was fulfilled by the Enlightenment, an earlier trend in culture, science and politics. The wars with the French Emperor Napoleon and the temporary loss of independence in the early 19th century did not inspire German poets to revolt and fight through poetry. They focused on the feelings, personality and spirituality of the individual taher than the nation.

Pictured: Napoleon granting of a constitution to the Duchy of Warsaw in a painting by Marcello Bacciarelli from 1811. For Poles, Napoleon was an object of gratitude for creating a substitute for their former state, even though it lasted only eight years. For Germans, Napoleon was an occupier and destroyer.

National Museum in Warsaw -

It was the individual, not the nation, that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, among others, dealt with in his works. He is considered the founder of modern German literature and the precursor of German Romanticism. Some compare Mickiewicz’s position in Polish collective memory to Goethe’s role as a symbol of national identity in German culture. The two had the opportunity to meet in Weimar in 1829, and Mickiewicz had previously translated several of Goethe’s works into Polish. However, the two writers had many differences, and it was not just Goethe’s age, who was 50 years older than Mickiewicz.

Pictured: Goethe’s house in Weimar in an anonymous engraving from 1856. It was here that Mickiewicz visited the German writer. Their conversation was about literature, and the men spared no compliments for each other despite their differences. Today the place houses the Goethe National Museum.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich -

Mickiewicz and Goethe differed in their understanding of the role of literature and the poet. For Goethe, the differences between nations, and therefore patriotism, were not important, so he did not address this topic. Also, Goethe treated faith in God more lightly than Mickiewicz and did not see it as a force for strengthening the community. Goethe distanced himself from current trends, avoiding making political slogans. Mickiewicz, on the other hand, devoted his literary and non-literary activities almost exclusively to publicizing the cause of Polish independence.

Pictured: Goethe in the Roman Campania in a 1787 painting by Johann Tischbein. The poet sought inspiration from the classical ideals of ancient art. Here, they are symbolized by shoots of young plants – a sign of the rebirth of universal values – that climb over Roman ruins.

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main -

Despite numerous translations and temporary periods of interest, Pan Tadeusz and other works by Mickiewicz did not become permanently popular reading among the Germans. Besides, their tastes were more easily captured by the works of French, Italian or Russian Romantics. Today it is difficult to find a living memory of Mickiewicz in German culture, and interest in him is usually shown by a small group of local scholars and lovers of Polish literature. One can, however, occasionally find Mickiewicz on monuments – like this one in Weimar, Goethe’s city.

Pictured: A bust of Adam Mickiewcz in Weimar’s Park an der Ilm. The sculpture, by Gerhard Thieme, stood in 1956 adjacent to monuments to other Romantic poets: the Hungarian Sándor Petőfi and the Russian Alexander Pushkin. Nearby is a statue of William Shakespeare, the patron saint of European literature. All the sculptures are just a few minutes’ walk from Goethe’s former home.

Wikipedia Commons -

PAN TADEUSZ OR TWO ROMANICISMS

An online exhibition of the Centre for Historical Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences in BerlinAuthor of the exhibition: Dr Maciej Gugała

Translated into German by: Agnieszka ZawadzkaThe visual material used in this exhibition comes from legal sources and was acquired in accordance with copyright law.

For those interested, we especially recommend publications that were helpful in the creation of the exhibition:

– Heinrich Olschowsky, “Johann Wolfgang von Goethe und Adam Mickiewicz – Poetische Gesetzgeber des kulturellen Kanons”, in: Deutsch-polnische Erinnerungsorte, ed. H. H. Hahn, R. Traba, vol. 3: Parallelen, Ferdinand Schöningh: Padeborn 2012, pp. 217–244;

– Tadeusz Namowicz, “Romantyzm”, in: Polacy i Niemcy. Historia, kultura, polityka, ed. A. Lawaty, Poznań 2003, pp. 346–354;

– Jerzy Kałążny, “Kiedy właściwie skończył się romantyzm? O (nie)trwałości paradygmatu romantycznego w kulturze polskiej i niemieckiej”, in: Interakcje. Leksykon komunikowania polsko-niemieckiego, ed. A. Gall, J. Grębowiec, J. Kalicińska, K. Kończal, I. Surynt, ATVT: Wrocław 2015, pp. 282–304;

– “Buddensieg i inni” – article on the Pan Tadeusz Museum website;

– as well as the Polish-language podcast on German translations of Pan Tadeusz recorded by the Pan Tadeusz Museum in Wrocław, https://soundcloud.com/user-306486307/buddensieg-i-inni-o-niemieckich-przekladach-pana-tadeusza-odc-6-w-ksiegarni;

– Neil MacGregor, Germany: Memories of a Nation, Knopf: New York 2014 (especially chapter “One Nation under Goethe”, pp. 131–152).On the poster: Fragment of Michał Elwiro Andriolli’s 1882 illustration to Pan Tadeusz, showing the main characters moving against a common enemy: the Russians.

National Library in Warsaw

Back

Back